Pete Barrett Plays and More

Full Length Plays

Two characters meet in the desert in AD 34. We don’t know who they are, but we assume them to be the Devil (The Walrus) and Jesus (The Carpenter). The Walrus has taken on the task of persuading the Carpenter to go out and found a new religion, athough it may end up in tears. In Act Two (Outside Looking In), The Walrus begins a psychoanalysis session with a descendant of Sigmund Freud. He proves to be a bit of a challenge, and ends up dazed and confused and threatening the spotlight operator. The play explores the idea of whether religion has any meaning if the supernatural doesn’t exist, whether Science is a suitable substitute for religion and whether psychoanalysis was anything more than just another fake religion. It references the Old and New Testaments, Freud, Elvis, Bill and Ted, Alice Through the Looking Glass, the Waste Land, Waiting for Godot, Casablanca, The Terminator and the Beatles – which is how it has come to be called ‘I am the Walrus’.

I am the Walrus was short-listed in the Paul Darby competition at the Questor’s Theatre in Ealing and was performed for a week at the Questor’s in November 2014.

MR SMITH: Let me paint a little picture for you. Amber went to sleep early last night – such a ruffled bed. I wonder why?. Silly girl, she forgot to take a little something. And even as we speak there’s a little spermatozoa swimming, swimming (He demonstrates) for his little life (Now he demonstrates with his two hands) this (His fisted hand) is a little egg, and this (His other hand) is our little friend. Even now in the dim distance he can see her. Their eyes meet across a crowded fallopian tube. They approach each other, they smile (He slams his hands together) they embrace. They become as one. Isn’t it romantic. I do so love a happy ending. Congratulations, daddy, it’s a boy.

GEORGE: (Shaking his head) I don’t believe you.

SMITH: If you don’t sign this paper, then you can say goodbye to your marriage, your sort-of-marriage, your home, your beloved little crack in the wall.

GEORGE: I won’t sign it. I won’t do it.

MR SMITH: The minute you sign, the egg will perish. It happens all the time.

GEORGE: I don’t believe you.

MR SMITH: Even now the cells divide – two, four, eight.. sixteen…thirty-two…sixty-four…

GEORGE: Wait a minute. This is an application for a bus pass.

MR SMITH: Is it?

GEORGE: I thought you said….

MR SMITH: I was having you on. You don’t really think people go round offering to buy your soul do you?

GEORGE: Then why do it?

MR SMITH: I was merely making a point, Mr Science-Has-An- Explanation-For-Everything. You wouldn’t sign it would you? You wouldn’t sell your soul. What does that tell you about what you really believe?

GEORGE: (Shaking his head) I don’t believe you.

SMITH: If you don’t sign this paper, then you can say goodbye to your marriage, your sort-of-marriage, your home, your beloved little crack in the wall.

GEORGE: I won’t sign it. I won’t do it.

MR SMITH: The minute you sign, the egg will perish. It happens all the time.

GEORGE: I don’t believe you.

MR SMITH: Even now the cells divide – two, four, eight.. sixteen…thirty-two…sixty-four…

GEORGE: Wait a minute. This is an application for a bus pass.

MR SMITH: Is it?

GEORGE: I thought you said….

MR SMITH: I was having you on. You don’t really think people go round offering to buy your soul do you?

GEORGE: Then why do it?

MR SMITH: I was merely making a point, Mr Science-Has-An- Explanation-For-Everything. You wouldn’t sign it would you? You wouldn’t sell your soul. What does that tell you about what you really believe?

Set in the gardens of a row of modern terraced houses, Something Wicked concerns itself with the arrival of a mysterious and malevolent Mr Smith who, within days of moving in, is wreaking havoc with the lives of neighbours, driving a wedge between Pandora and Michael, encouraging George into an extra marital dalliance with his neighbour’s daughters and digging up dark memories for Phyllis and Willie. But who the devil is he?

“The author confidently handles dialogue, swiftly establishing characters and their relationships whilst at the same time providing lots of laughs. The characters are comic types easy to recognise, but with sufficient definitions of character and not caricatures. Staging is well thought out probably for a larger theatre (all those gardens) and given the theatricality with Mr Smith’s explosions and magic tricks. The special effects are a good way of keeping the audience on the edge of their seats.” (Bristol Old Vic)

My son is gay. I’ve got to understand that. Otherwise you’re going to disappear. I don’t want that. I’m having enough trouble getting used to the fact that you’ve grown up. I don’t want my son to be a gay bloke living up in London going to Kylie Minogue concerts, I want you to be Tim, playing in the sandpit in the garden, getting covered in mud. I want to go back to when you were little, when I could carry you upstairs on one arm. But you’re not that kid anymore, you’re a man. And you’re gay. And you’ve gone to live on the other side of the world.

“This play has a very strong premise, which brims with conflict between the old and the new, the land and the city. We particularly enjoyed the humour of the writing which made us laugh out loud, and the idiosyncrasies of the characters. The characters are etched with delicacy and contradiction: Gran has moments of lucidity and David manages a heart to heart with his son in spite of himself. They subvert our expectations effectively, but we do feel the release of information might be even more restrained in order to further exploit the tension. Any anxiety Tim has about revealing his sexuality, to his parents reaction/dismissal of it feel quickly and articulately expressed.” (Royal Court)

BOURNE: It seems that if I free this girl from an unwanted pregnancy, if I save her the burden of bearing a child conceived by the most brutal of rapes, I will be prosecuted.

ROXBURGH: That’s about the size of it, sir. BOURNE: And what do you think of such a law?

ROXBURGH: It’s not my place to think about the law, sir.

BOURNE: So if you see some starving beggar steal a loaf of stale bread, you must prosecute him, must you? You have no discretion in the matter?

ROXBURGH: Very little, sir. If I know of a crime then I must act upon that knowledge.

BOURNE: If I should be prosecuted for this termination then my punishment could potentially be greater than that visited on those men who raped a children rape and caused the pregnancy.

ROXBURGH:That’s a matter for the judge, sir

ROXBURGH: That’s about the size of it, sir. BOURNE: And what do you think of such a law?

ROXBURGH: It’s not my place to think about the law, sir.

BOURNE: So if you see some starving beggar steal a loaf of stale bread, you must prosecute him, must you? You have no discretion in the matter?

ROXBURGH: Very little, sir. If I know of a crime then I must act upon that knowledge.

BOURNE: If I should be prosecuted for this termination then my punishment could potentially be greater than that visited on those men who raped a children rape and caused the pregnancy.

ROXBURGH:That’s a matter for the judge, sir

This play won the Full Circle Radio Play Competition 2017 and can be heard with this link.

Because I am the King. And Poe is a sycophant. … Yes, yes, Poe, that will do. He is attempting to ingratiate himself with me knowing as he does that as a poet, indeed as a person, he is hopelessly unworthy. But at least he knows his place. He understands the nature of power. Unfortunately because I have compassion and rule with humanity, I am surrounded with people unable to grasp this simple conceit. I have advisers who advise when they should agree. I have courtiers who criticise when they should flatter. When did I last have a whim indulged? If I decided to make my horse chancellor – as is my right – Would I hear ‘Yes, majesty’, ‘Splendid idea, highness’. No. I would not. I would hear ‘You can’t do that, he can’t work the abacus’

We can dig millions of tons of coal from half a mile underground better than anyone else in the world. But nobody wants it. It stinks, it fills the air wi’ smoke, kills trees. Nobody wants it. Nobody needs it. All we’re doing is building bloody great pyramids of coal. All over the country you’ve got these great big black heaps. But we can’t stop cause that’s what we’re good at – digging coal.

EMMA:You could do other things.

FRANK:No I can’t.

EMMA:You can.

FRANK:In a thousand years time they’ll find those pyramids and they’ll say ‘Why?’, ‘What are they for?’. Maybe it won’t even take that long. EMMA:They’ll think we buried Margaret Thatcher under one.

FRANK:You’d need a big one – t’keep that cow under. No. They’re already turning the mines into museums. They’ll hire us back to pretend we’re digging coal so’s gangs of schoolkids can ‘ave a look round. Look at that. That’s what it’s like digging coal. That’s what it’s like ‘aving a job

EMMA:You could do other things.

FRANK:No I can’t.

EMMA:You can.

FRANK:In a thousand years time they’ll find those pyramids and they’ll say ‘Why?’, ‘What are they for?’. Maybe it won’t even take that long. EMMA:They’ll think we buried Margaret Thatcher under one.

FRANK:You’d need a big one – t’keep that cow under. No. They’re already turning the mines into museums. They’ll hire us back to pretend we’re digging coal so’s gangs of schoolkids can ‘ave a look round. Look at that. That’s what it’s like digging coal. That’s what it’s like ‘aving a job

“This really is a very witty well-written play. The characters are extremely well drawn and the writer’s skill has been in giving each of them their own pace, the volatile, unreasonableness of Rachel constantly clashes against Frank’s belief in traditional systems of values, and yet he too has his contradictions and an ability to laugh at himself.

Robert Wolfe, a philanderer with an acid tongue, who has used his good looks, wit and charm, to indulge in a life of indulgence, reaches the age of sixty and finds he has cancer. His one area of regret in life is his estrangement from his three daughters. He determines that this illness will give him the impetus, the money and the means, to seek reconciliation with his daughters. He will at last ‘come home’.

In exchange for his money, his three daughters, who lead very different lives, agree to look after him in his remaining months. However, as if he moves from daughter to daughter, rather than reconciliation, he finds anger and hurt as he, once again, disrupts their lives.

Unable to find redemption in his family, Robert ends up on the very fringes of society where he does, in the end, find a kind of peace.

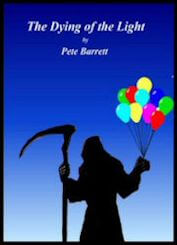

The Dying of the Light is a dark comedy whose plot-line has echoes of King Lear.

Premiered at the Wolsey Theater Ipswich in 1997.

“Pete Barrett an East Anglian Playwright desrves wide recognition for his vivid and imaginative writing” Evening Star

A burned out pop star hides away in a mansion where he lives in fear of the peacocks.

ADAM: OK. So. Money.

GINA: A credit card would be OK.

ADAM: Don’t use them.

GINA: Cheque.

ADAM: I did have a cheque book once.

GINA: What do you use for money?

ADAM: Bill. I use Bill for money.

GINA: Where’s Bill.

ADAM: Bill’s not talking to me. I told him I’d written eight songs for the new album.

GINA: And you hadn’t?

ADAM: No.

GINA: How many had you written?

ADAM: Roughly?

GINA: Yes roughly.

ADAM: None.

GINA: You’ve written some lovely songs. I love that one about the diner, in Carolina.

ADAM: Yeah that was good wasn’t it. Only it wasn’t in Carolina. It was in Georgia. Didn’t rhyme see.

GINA: I’m very disillusioned.

ADAM: You, and the rest of the world darling.

GINA: A credit card would be OK.

ADAM: Don’t use them.

GINA: Cheque.

ADAM: I did have a cheque book once.

GINA: What do you use for money?

ADAM: Bill. I use Bill for money.

GINA: Where’s Bill.

ADAM: Bill’s not talking to me. I told him I’d written eight songs for the new album.

GINA: And you hadn’t?

ADAM: No.

GINA: How many had you written?

ADAM: Roughly?

GINA: Yes roughly.

ADAM: None.

GINA: You’ve written some lovely songs. I love that one about the diner, in Carolina.

ADAM: Yeah that was good wasn’t it. Only it wasn’t in Carolina. It was in Georgia. Didn’t rhyme see.

GINA: I’m very disillusioned.

ADAM: You, and the rest of the world darling.